"Learn thou from him."--This story was told by the Master while at Jetavana, about the Elder named Tissa the Squire's Son. Tradition says that one day thirty young gentlemen of Sāvatthi, who were all friends of one another, took perfumes and flowers and robes, and set out with a large retinue to Jetavana, in order to hear the Master preach. Arrived at Jetavana, they sat awhile in the several enclosures--in the enclosure of the Iron-wood trees, in the enclosure of the Sal-trees, and so forth,--till at evening the Master passed from his fragrant sweet-smelling perfumed chamber to the Hall of Truth and took his seat on the gorgeous Buddha-seat. Then, with their following, these young men went to the Hall of Truth, made an offering of perfumes and flowers, bowed down at his feet--those blessed feet that were glorious as full-blown lotus-flowers, and bore imprinted on the sole the Wheel!--and, taking their seats, listened to the Truth. Then the thought came into their minds, "Let us take the vows, so far as we understand the Truth preached by the Master." Accordingly, when the Blessed One left the Hall, they approached him and with due obeisance asked to be admitted to the Brotherhood; and the Master admitted them to the Brotherhood. Winning the favour of their teachers and directors they received full Brotherhood, and after five years' residence with their teachers and directors, by which time they had got by heart the two Abstracts, had come to know what was proper and what was improper, had learnt the three modes of expressing thanks, and had stitched and dyed robes. At this stage, wishing to embrace the ascetic life, they obtained the consent of their teachers and directors, and approached the Master. Bowing before him they took their seats, saying, "Sir, we are troubled by the round of existence, dismayed by birth, decay, disease, and death; give us a theme, by thinking on which we may get free from the elements which occasion existence." The Master turned over in his mind the eight and thirty themes of thought, and therefrom selected a suitable one, which he expounded to them. And then, after getting their theme from the Master, they bowed and with a ceremonious farewell passed from his presence to their cells, and after gazing on their teachers and directors went forth with bowl and robe to embrace the ascetic life.

Now amongst them was a Brother named the Elder Tissa the Squire's Son, a weak and irresolute man, a slave to the pleasures of the taste. Thought he to himself, "I shall never be able to live in the forest, to strive with strenuous effort, and subsist on doles of food. What is the good of my going? I will turn back." And so he gave up, and after accompanying those Brothers some way he turned back. As to the other Brothers, they came in the course of their alms-pilgrimage through Kosala to a certain border-village, [317] hard by which in a wooded spot they kept the Rainy-season, and by three months' striving and wrestling got the germ of Discernment and won Arahatship, making the earth shout for joy. At the end of the Rainy-season, after celebrating the Pavāraṇā festival, they set out thence to announce to the Master the attainments they had won, and, coming in due course to Jetavana, laid aside their bowls and robes, paid a visit to their teachers and directors, and, being anxious to see the Blessed One, went to him and with due obeisance took their seats. The Master greeted them kindly and they announced to the Blessed One the attainments they had won, receiving praise from him. Hearing the Master speaking in their praise, the Elder Tissa the Squire's Son was filled with a desire to live the life of a recluse all by himself. Likewise, those other Brothers asked and received the Master's permission to return to dwell in that self-same spot in the forest. And with due obeisance they went to their cells.

Now the Elder Tissa the Squire's Son that very night was inflated with a yearning to begin his austerities at once, and whilst practising with excessive zeal and ardour the methods of a recluse and sleeping in an upright posture by the side of his plank-bed, soon after the middle watch of the night, round he turned and down he fell, breaking his thigh-bone; and severe pains set in, so that the other Brothers had to nurse him and were debarred from going.

Accordingly, when they appeared at the hour for waiting on the Buddha, he asked them whether they had not yesterday asked his leave to start to-day.

"Yes, sir, we did; but our friend the Elder Tissa the Squire's Son, while rehearsing the methods of a recluse with great vigour but out of season, dropped off to sleep and fell over, breaking his thigh; and that is why our departure has been thwarted." "This is not the first time, Brethren," said the Master, "that this man's backsliding has caused him to strive with unseasonable zeal, and thereby to delay your departure; he delayed your departure in the past also." And hereupon, at their request, he told this story of the past.

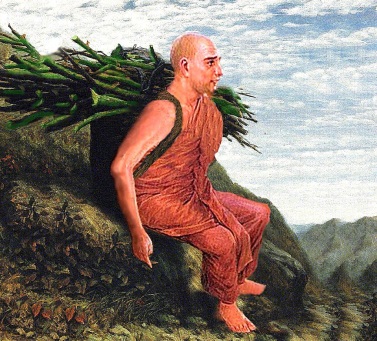

Once on a time at Takkasilā in the kingdom of Gandhāra the Bodhisatta was a teacher of world-wide fame, with 500 young brahmins as pupils. One day these pupils set out for the forest to gather firewood for their master, and busied themselves in gathering sticks. Amongst them was a lazy fellow who came on a huge forest tree, which he imagined to be dry and rotten. So he thought that he could safely indulge in a nap first, and at the last moment climb up [318] and break some branches off to carry home. Accordingly, he spread out his outer robe and fell asleep, snoring loudly. All the other young brahmins were on their way home with their wood tied up in faggots, when they came upon the sleeper. Having kicked him in the back till he awoke, they left him and went their way. He sprang to his feet, and rubbed his eyes for a time. Then, still half asleep, he began to climb the tree. But one branch, which he was tugging at, snapped off short; and, as it sprang up, the end struck him in the eye. Clapping one hand over his wounded eye, he gathered green boughs with the other. Then climbing down, he corded his faggot, and after hurrying away home with it, flung his green wood on the top of the others' faggots.

That same day it chanced that a country family invited the master to visit them on the morrow, in order that they might give him a brahmin-feast. And so the master called his pupils together, and, telling them of the journey they would have to make to the village on the morrow, said they could not go fasting. "So have some rice-gruel made early in the morning," said he; "and eat it before starting. There you will have food given you for yourselves and a portion for me. Bring it all home with you."

So they got up early next morning and roused a maid to get them their breakfast ready betimes. And off she went for wood to light the fire. The green wood lay on the top of the stack, and she laid her fire with it. And she blew and blew, but could not get her fire to burn, and at last the sun got up. "It's broad daylight now," said they, "and it's too late to start." And they went off to their master.

"What, not yet on your way, my sons?" said he. "No, sir; we have not started." "Why, pray?" "Because that lazy so-and-so, when he went wood-gathering with us, lay down to sleep under a forest-tree; and, to make up for lost time, he climbed up the tree in such a hurry that he hurt his eye and brought home a lot of green wood, which he threw on the top of our faggots. So, when the maid who was to cook our rice-gruel went to the stack, she took his wood, thinking it would of course be dry; and no fire could she light before the sun was up. And this is what stopped our going."

Hearing what the young brahmin had done, the master exclaimed that a fool's doings had caused all the mischief, and repeated this stanza:--

[319] Learn thou from him who tore green branches down,

That tasks deferred are wrought in tears at last.

Such was the Bodhisatta's comment on the matter to his pupils; and at the close of a life of charity and other good works he passed away to fare according to his deserts.

Said the Master, "This is not the first time, Brethren, that this man has thwarted you; he did the like in the past also." His lesson ended, he shewed the connexion and identified the Birth by saying, "The Brother who has broken his thigh was the young brahmin of those days who hurt his eye; the Buddha's followers were the rest of the young brahmins; and I myself was the brahmin their master."

Now amongst them was a Brother named the Elder Tissa the Squire's Son, a weak and irresolute man, a slave to the pleasures of the taste. Thought he to himself, "I shall never be able to live in the forest, to strive with strenuous effort, and subsist on doles of food. What is the good of my going? I will turn back." And so he gave up, and after accompanying those Brothers some way he turned back. As to the other Brothers, they came in the course of their alms-pilgrimage through Kosala to a certain border-village, [317] hard by which in a wooded spot they kept the Rainy-season, and by three months' striving and wrestling got the germ of Discernment and won Arahatship, making the earth shout for joy. At the end of the Rainy-season, after celebrating the Pavāraṇā festival, they set out thence to announce to the Master the attainments they had won, and, coming in due course to Jetavana, laid aside their bowls and robes, paid a visit to their teachers and directors, and, being anxious to see the Blessed One, went to him and with due obeisance took their seats. The Master greeted them kindly and they announced to the Blessed One the attainments they had won, receiving praise from him. Hearing the Master speaking in their praise, the Elder Tissa the Squire's Son was filled with a desire to live the life of a recluse all by himself. Likewise, those other Brothers asked and received the Master's permission to return to dwell in that self-same spot in the forest. And with due obeisance they went to their cells.

Now the Elder Tissa the Squire's Son that very night was inflated with a yearning to begin his austerities at once, and whilst practising with excessive zeal and ardour the methods of a recluse and sleeping in an upright posture by the side of his plank-bed, soon after the middle watch of the night, round he turned and down he fell, breaking his thigh-bone; and severe pains set in, so that the other Brothers had to nurse him and were debarred from going.

Accordingly, when they appeared at the hour for waiting on the Buddha, he asked them whether they had not yesterday asked his leave to start to-day.

"Yes, sir, we did; but our friend the Elder Tissa the Squire's Son, while rehearsing the methods of a recluse with great vigour but out of season, dropped off to sleep and fell over, breaking his thigh; and that is why our departure has been thwarted." "This is not the first time, Brethren," said the Master, "that this man's backsliding has caused him to strive with unseasonable zeal, and thereby to delay your departure; he delayed your departure in the past also." And hereupon, at their request, he told this story of the past.

Once on a time at Takkasilā in the kingdom of Gandhāra the Bodhisatta was a teacher of world-wide fame, with 500 young brahmins as pupils. One day these pupils set out for the forest to gather firewood for their master, and busied themselves in gathering sticks. Amongst them was a lazy fellow who came on a huge forest tree, which he imagined to be dry and rotten. So he thought that he could safely indulge in a nap first, and at the last moment climb up [318] and break some branches off to carry home. Accordingly, he spread out his outer robe and fell asleep, snoring loudly. All the other young brahmins were on their way home with their wood tied up in faggots, when they came upon the sleeper. Having kicked him in the back till he awoke, they left him and went their way. He sprang to his feet, and rubbed his eyes for a time. Then, still half asleep, he began to climb the tree. But one branch, which he was tugging at, snapped off short; and, as it sprang up, the end struck him in the eye. Clapping one hand over his wounded eye, he gathered green boughs with the other. Then climbing down, he corded his faggot, and after hurrying away home with it, flung his green wood on the top of the others' faggots.

That same day it chanced that a country family invited the master to visit them on the morrow, in order that they might give him a brahmin-feast. And so the master called his pupils together, and, telling them of the journey they would have to make to the village on the morrow, said they could not go fasting. "So have some rice-gruel made early in the morning," said he; "and eat it before starting. There you will have food given you for yourselves and a portion for me. Bring it all home with you."

So they got up early next morning and roused a maid to get them their breakfast ready betimes. And off she went for wood to light the fire. The green wood lay on the top of the stack, and she laid her fire with it. And she blew and blew, but could not get her fire to burn, and at last the sun got up. "It's broad daylight now," said they, "and it's too late to start." And they went off to their master.

"What, not yet on your way, my sons?" said he. "No, sir; we have not started." "Why, pray?" "Because that lazy so-and-so, when he went wood-gathering with us, lay down to sleep under a forest-tree; and, to make up for lost time, he climbed up the tree in such a hurry that he hurt his eye and brought home a lot of green wood, which he threw on the top of our faggots. So, when the maid who was to cook our rice-gruel went to the stack, she took his wood, thinking it would of course be dry; and no fire could she light before the sun was up. And this is what stopped our going."

Hearing what the young brahmin had done, the master exclaimed that a fool's doings had caused all the mischief, and repeated this stanza:--

[319] Learn thou from him who tore green branches down,

That tasks deferred are wrought in tears at last.

Such was the Bodhisatta's comment on the matter to his pupils; and at the close of a life of charity and other good works he passed away to fare according to his deserts.

Said the Master, "This is not the first time, Brethren, that this man has thwarted you; he did the like in the past also." His lesson ended, he shewed the connexion and identified the Birth by saying, "The Brother who has broken his thigh was the young brahmin of those days who hurt his eye; the Buddha's followers were the rest of the young brahmins; and I myself was the brahmin their master."