One day the king said, "A present has been brought: take this to the Brethren," and sent it to the refectory. An answer was brought that no Brethren were there in the refectory. "Where are they gone?" he asked. They were sitting in their friends' houses to eat, was the reply. So the king after his morning meal came into the Master's presence, and asked him, "Good Sir, what is the best kind of food?" "The food of friendship is the best, great king," said he; "even sour rice-gruel given by a friend becomes sweet." "Well, Sir, and with whom do the Brethren find friendship?" "With their kindred, great king, or with the Sakya families." Then the king thought, what if he were to make a Sakya girl his queen-consort: then the Brethren would be his friends, as it were with their own kindred.

So rising fr om his seat, he returned to the palace, and sent a message to Kapilavatthu to this effect: "Please give me one of your daughters in marriage, for I wish to become connected with your family." On receipt of this message the Sakyas gathered together and deliberated. "We live in a place subject to the authority of the king of Kosala; if we refuse a daughter, he will be very angry, and if we give her, the custom of our clan will be broken. What are we to do?" Then Mahānāma said to them, "Do not trouble about it. I have a daughter, named Vāsabhakhattiyā. Her mother is a slave woman, Nāgamuṇḍā by name; she is some sixteen years of age, of great beauty and auspicious prospects, and by her father's side noble. We will send her, as a girl nobly born." The Sakyas agreed, and sent for the messengers, and said they were willing to give a daughter of the clan, and that they might take her with them at once. But the messengers reflected, "These Sakyas are desperately proud, in matters of birth. Suppose they should send a girl who was not of them, and say that she was so? We will take none but one who eats along with them." So they replied, "Well, we will take her, but we will take one who eats along with you."

The Sakyas assigned a lodging for the messengers, and then wondered what to do. Mahānāma said: "Now do not trouble about it; I will find a way. At my mealtime bring in Vāsabhakhattiyā drest up in her finery; then just as I have taken one mouthful, produce a letter, and say, My lord, such a king has sent you a letter; be pleased to hear his message at once."

So Mahānāma sent away his daughter in great pomp. The messengers brought her to Sāvatthi, and said that this maiden was the true-born daughter of Mahānāma. The king was pleased, and caused the whole city to be decorated, and placed her upon a pile of treasure, and by a ceremonial sprinkling made her his chief queen. She was dear to the king, and beloved.

In a short time the queen conceived, and the king caused the proper treatment to be used; and at the end of ten months, she brought forth a son whose colour was a golden brown. On the day of his naming, the king sent a message to his grandmother, saying, "A son has been born to Vāsabhakhattiyā, daughter of the Sakya king; what shall his name be?" Now the courtier who was charged with this message was slightly deaf; but he went and told the king's grandmother. When she heard it, she said, "Even when Vāsabhakhattiyā had never borne a son, she was more than all the world; and now she will be the king's darling." The deaf man did not hear the word "darling" aright, but thought she said "Viḍūḍabha; "so back he went to the king, and told him that he was to name the prince Viḍūḍabha. This, the king thought, must be some ancient family name, and so named him Viḍūḍabha.

After this the prince grew up treated as a prince should be.

When he was at the age of seven years, having observed how the other princes received presents of toy elephants and horses and other toys fr om the family of their mothers' fathers, the lad said to his mother, "Mother, the rest of them get presents fr om their mothers' family, but no one sends me anything. Are you an orphan?" Then she replied, "My boy, your grandsires are the Sakya kings, but they live a long way off, and that is why they send you nothing." Again when he was sixteen, he said, "Mother, I want to see your father's family." "Don't speak of it, child," she said. "What will you do when you get there?" But though she put him off, he asked her again and again. At last his mother said, "Well, go then." So the lad got his father's consent, and set out with a number of followers. Vāsabhakhattiyā sent on a letter before him to this effect: "I am living here happily; let not my masters tell him anything of the secret." But the Sakyas, on hearing of the coming of Viḍūḍabha, sent off all their young children into the country. "It is impossible," said they, "to receive him with respect."

When the Prince arrived at Kapilavatthu, the Sakyas had assembled in the royal rest-house. The Prince approached the rest-house, and waited. Then they said to him, "This is your mother's father, this is her brother," pointing them out. He walked fr om one to the other, saluting them. But although he bowed to them till his back ached, not one of them vouchsafed a greeting; so he asked, "Why is it that none of you greet me?" The Sakyas replied, "My dear, the youngest princes are all in the country;" then they entertained him grandly.

After a few days' stay, he set out for home with all his retinue. Just then a slave woman washed the seat which he had used in the rest-house with milk-water, saying insultingly, "Here's the seat where sat the son of Vāsabhakhattiyā, the slave girl!" A man who had left his spear behind was just fetching it, when he overheard the abuse of Prince Viḍūḍabha. He asked what it meant. He was told that Vāsabhakhattiyā was born of a slave to Mahānāma the Sakya. This he told to the soldiers: a great uproar arose, all shouting—"Vāsabhakhattiyā is a slave woman's daughter, so they say!" The Prince heard it. "Yes," thought he, "let them pour milk-water over the seat I sat in, to wash it! When I am king, I will wash the place with their hearts' blood!"

When he returned to Sāvatthi, the courtiers told the whole matter to the king. The king was enraged against the Sakyas for giving him a slave's daughter to wife. He cut off all allowances made to Vāsabhakhattiyā and her son, and gave them only what is proper to be given to slave men and women.

Some few days later the Master came to the palace, and took a seat. The king approached him, and with a greeting said, "Sir, I am told that your clansmen gave me a slave's daughter to wife. I have cut off their allowances, mother and son, and grant them only what slaves would get." Said the Master, "The Sakyas have done wrong, O great king! If they gave any one, they ought to have given a girl of their own blood. But, O king, this I say: Vāsabhakhattiyā is a king's daughter, and in the house of a noble king she has received the ceremonial sprinkling; Viḍūḍabha too was begotten by a noble king. Wise men of old have said, what matters the mother's birth? The birth of the father is the measure: and to a poor wife, a picker of sticks, they gave the position of queen consort; and the son born of her obtained the sovereignty of Benares, twelve leagues in extent, and became King Kaṭṭha-vāhana, the Wood-carrier:" whereupon he told him the story of the Kaṭṭhahāri Birth.

When the king heard this speech he was pleased; and saying to himself, "The father's birth is the measure of the man," he again gave mother and son the treatment suited to them.

Now the king's commander-in-chief was a man named Bandhula. His wife, Mallikā, was barren, and he sent her away to Kusināra, telling her to return to her own family. "I will go," said she, "when I have saluted the Master." She went to Jetavana, and greeting the Tathāgata stood waiting on one side. "Where are you going?" he asked. She replied, "My husband has sent me home, Sir." "Why?" asked the Master. "I am barren, Sir, I have no son." "If that is all," said he, "there is no reason why you should go. Return." She was much pleased, and saluting the Master went home again. Her husband asked her why she had come back. She answered, "The Dasabala sent me back, my lord." "Then," said the commander-in-chief, "the Tathāgata must have seen good reason." The woman soon after conceived, and when her cravings began, told him of it. "What is it you want?" he asked. "My lord," said she, "I desire to go and, bathe and drink the water of the tank in Vesāli City where the families of the kings get water for the ceremonial sprinkling." The commander-in-chief promised to try. Seizing his bow, strong as a thousand bows, he put his wife in a chariot, and left Sāvatthi, and drove his chariot to Vesālī.

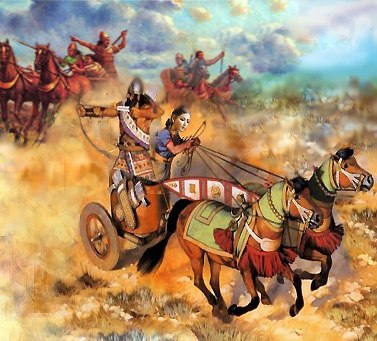

Now at this time there lived close to the gate a Licchavi named Mahāli, who had been educated by the same teacher as the king of Kosala's general, Bandhula. This man was blind, and used to advise the Licchavis on all matters temporal and spiritual. Hearing the clatter of the chariot as it went over the threshold, he said, "The noise of the chariot of Bandhula the Mallian! This day there will be fear for the Licchavis!" By the tank there was set a strong guard, within and without; above it was spread an iron net; not even a bird could find room to get through. But the general, dismounting from his car, put the guards to flight with the blows of his sword, and burst through the iron network, and in the tank bathed his wife and gave her to drink of the water; then after bathing himself, he set Mallikā in the chariot, and left the town, and went back by the way he came.

The guards went and told all to the Licchavis. Then were the kings of the Licchavis angry; and five hundred of them, mounted in five hundred chariots, departed to capture Bandhula the Mallian. They informed Mahāli of it, and he said, "Go not! for he will slay you all." But they said, "Nay, but we will go." "Then if you come to a place wh ere a wheel has sunk up to the nave, you must return. If you return not then, return back from that place when you hear the noise of a thunderbolt. If then you turn not, turn back from that place wh ere you shall see a hole in front of your chariots. Go no further!" But they did not turn back according to his word, but pursued on and on. Mallikā espied them and said, "There are chariots in sight, my lord." "Then tell me," said he, "when they all look like one chariot." When they all in a line looked like one, she said, "My lord, I see as it were the head of one chariot." "Take the reins, then," said he, and gave the reins into her hand: he stood upright in the chariot, and strung his bow. The chariot-wheel sank into the earth nave-deep. The Licchavis came to the place, and saw it, but turned not back. The other went on a little further, and twanged the bow string; then came a noise as the noise of a thunderbolt, yet even then they turned not, but pursued on and on. Bandhula stood up in the chariot and sped a shaft, and it cleft the heads of all the five hundred chariots, and passed right through the five hundred kings in the place wh ere the girdle is fastened, and then buried itself in the earth. They not perceiving that they were wounded pursued still, shouting, "Stop, holloa, stop!" Bandhula stopt his chariot, and said, "You are dead men, and I cannot fight with the dead." "What!" said they, "dead, such as we now are?" "Loose the girdle of the first man," said Bandhula.

They loosed his girdle, and at the instant the girdle was loosed, he fell dead. Then he said to them, "You are all of you in the same condition: go to your homes, and set in order what should be ordered, and give your directions to your wives and families, and then doff your armour." They did so, and then all of them gave up the ghost.

And Bandhula conveyed Mallikā to Sāvatthi. She bore twin sons sixteen times in succession, and they were all mighty men and heroes, and became perfected in all manner of accomplishments. Each one of them had a thousand men to attend him, and when they went with their father to wait on the king, they alone filled the courtyard of the palace to overflowing.

One day some men who had been defeated in court on a false charge, seeing Bandhula approach, raised a great outcry, and informed him that the judges of the court had supported a false charge. So Bandhula went into the court, and judged the case, and gave each man his own. The crowd uttered loud shouts of applause. The king asked what it meant, and on hearing was much pleased; all those officers he sent away, and gave Bandhula charge of the judgement court, and thenceforward he judged aright. Then the former judges became poor, because they no longer received bribes, and they slandered Bandhula in the king's ear, accusing him of aiming at the kingdom himself. The king listened to their words, and could not control his suspicions. "But," he reflected, "if he be slain here, I shall be blamed." He suborned certain men to harry the frontier districts; then sending for Bandhula, he said, "The borders are in a blaze; go with your sons and capture the brigands." With him he also sent other men sufficient, mighty men of war, with instructions to kill him and his two-and-thirty sons, and cut off their heads, and bring them back.

While he was yet on the way, the hired brigands got wind of the general's coming, and took to flight. He settled the people of that district in their homes, and quieted the province, and set out for home. Then when he was not far from the city, those warriors cut off his head and the heads of his sons.

On that day Mallikā had sent an invitation to the two chief disciples along with five hundred of the Brethren. Early in the forenoon a letter was brought to her, with news that her husband and sons had lost their heads. When she heard this, without a word to a soul, she tucked the letter in her dress, and waited upon the company of the Brethren. Her attendants had given rice to the Brethren, when bringing in a bowl of ghee they happened to break the bowl just in front of the Elders. Then the Captain of the Faith said, "Pots are made to be broken; do not trouble about it." The lady produced her letter from the fold of her dress, saying, "Here I have a letter informing me that my husband and his two-and-thirty sons have been beheaded. If I do not trouble about that, am I likely to trouble when a bowl is broken?" The Captain of the Faith now began, "Unseen, unknown," and so forth, then rising from his seat uttered a discourse, and went home. She summoned her two-and-thirty daughters-in-law, and to them said, "Your husbands, though innocent, have reaped the fruit of their former deeds. Do not you grieve, nor commit a sin of the soul worse even than the king's." This was her advice. The king's spies hearing this speech brought word to him that they were not angry. Then the king was distrest, and went to her dwelling, and craving pardon of Mallikā and her sons' wives, offered a boon. She replied, "Be it accepted." She set out the funeral feast, and bathed, and then went before the king. "My lord," said she, "you granted me a boon. I want nothing but this, that you permit my two-and-thirty daughters-in-law and me to go back to our own homes." The king consented. Each of her two-and-thirty sons' wives she sent away to her home, and herself returned to the home of her family in the city of Kusināra. And the king gave the post of commander-in-chief to one Dīgha-kārāyana, sister's son to the general Bandhula. But he went about picking faults in the king and saying, "He murdered my uncle."

Ever after the murder of the innocent Bandhula the king was devoured by remorse, and had no peace of mind, felt no joy in being king. At that time the Master dwelt near a country town of the Sakyas, named Uḷumpa. Thither went the king, pitched a camp not far from the park, and with a few attendants went to the monastery to salute the Master. The five symbols of royalty he handed to Kārāyana, and alone entered the Perfumed Chamber. All that followed must be described as in the Dhammacetiya Sutta. When he entered the Perfumed Chamber, Kārāyana took those symbols of royalty, and made Viḍūḍabha king; and leaving behind for the king one horse and a serving woman, he went to Sāvatthi.

After a pleasant conversation with the Master, the king on his return saw no army. He enquired of the woman, and learnt what had been done. Then set out for the city of Rājagaha, resolved to take his nephew with him, and capture Viḍūḍabha. It was late when he came to the city, and the gates were shut: and lying down in a shed, exhausted by exposure to wind and sun, he died there.

When the night began to grow brighter, the woman began to wail, "My lord, the king of Kosala is past help!" The sound was heard, and news came to the king. He performed the obsequies of his uncle with great magnificence.

Viḍūḍabha once firmly established on the throne remembered that grudge of his, and determined to destroy the Sakyas one and all; to which end he set out with a large army. That day at dawn the Master, looking forth over the world, saw destruction threatening his kin. "I must help my kindred," thought he. In the forenoon he went in search of alms, then after returning from his meal lay down lion-like in his Perfumed Chamber, and in the evening-time, having past through the air to a spot near Kapilavatthu, sat beneath a tree that gave scanty shade. Hard by that place, a huge and shady banyan tree stood on the boundary of Viḍūḍabha's realms. Viḍūḍabha seeing the Master approached and saluting him, said, "Why, Sir, are sitting under so thin a tree in all this heat? Sit beneath this shady banyan, Sir." He replied, "Let be, O king! the shade of my kindred keeps me cool."—"The Master," thought the other, "must have come here to protect his clansmen." So he saluted the Master, and returned again to Sāvatthi. And the Master rising went to Jetavana. A second time the king called to mind his grudge against the Sakyas, a second time he set forth, and again saw the Master seated in the same place, then again returned. A fourth time he set out; and the Master, scanning the former deeds of the Sakyas, perceived that nothing could do away with the effect of their evildoing, in casting poison into the river; so he did not go thither the fourth time. Then king Viḍūḍabha slew all the Sakyas, beginning with babes at the breast, and with their hearts' blood washed the bench, and returned.

On the day after the Master had gone out for the third time and returned, he, having gone his rounds for alms, and his meal over, was resting in his Perfumed Chamber, the Brethren gathered from all directions into the Hall of Truth, and seating themselves, began to tell of the virtues of the Great Being:."Sirs, the Master but showed himself, and turned the king back, and set free his kinsmen from fear of death. A helpful friend is the Master to his clan!" The Master entered, and asked what they talked of as they sat there. They told him. Then he said, "Not now only, Brethren, does the Tathāgata act for the benefit of his kinsmen; he did the same long ago." With these words, he told a story of the past.

Once upon a time, when Brahmadatta ruled as king in Benares, and observed the Ten Royal Virtues, he thought to himself: "All over India the kings live in palaces supported by many a column. There is no marvel, then, in a palace supported by many columns; but what if I make a palace with one column only to support it? Then I shall be the chiefest king of all kings!" So he summoned his builders, and told them to build him a magnificent palace supported on one column. "Very good," said they, and away they went into the forest.

There they beheld many a tree, straight and great, worthy to be the single column of such a palace."Here are these trees," said they, "but the road is rough, and we can never transport them; we will go ask the king about it." When they did so, the king said, "By hook or by crook you must bring them, and that quickly." But they answered, "Neither by hook nor by crook can the thing be done." "Then," said the king, "search for a tree in my park."

The builders went to the park, and there they espied a lordly sal tree, straight and well grown, worshipt by village and town, and to it the royal family also were wont to pay tribute and worship; and they told the king. Said the king, "In my park ye have found me a tree: good—go and cut it down." "So be it," said they, and repaired to the park, with their hands full of perfumed garlands and the like; then hanging upon it a five-spray garland, and encircling it with a string, fastening to it a nosegay of flowers, and kindling a lamp, they did worship, explaining, "On the seventh day from now we shall cut down this tree: it is the king's command so to cut it down. Let the deities who dwell in this tree go elsewhither, and not unto us be the blame."

The god who dwelt in the tree bearing this, thought to himself: "These builders are determined to cut down this tree, and to destroy my place of dwelling. Now my life only lasts as long as this my abiding place. And all the young sal trees that stand around this, wh ere dwell the deities my kinsfolk, and they are many, will be destroyed. My own destruction does not touch me so near as the destruction of my children: therefore I must protect their lives." Accordingly at the hour of midnight, adorned in divine splendour, he entered into the magnificent chamber of the king, and filling the whole chamber with a bright radiance, stood weeping beside the king's pillow. At sight of him the king, overcome by terror, uttered the first stanza:

"Who art thou, standing high in air, with heavenly vesture swathed: Whence come thy fears, why flow the tears in which thine eyes are bathed?"

On hearing which the king of the gods repeated two stanzas:

"Within thy realm, O King, they know me as the Lucky Tree: For sixty thousand years I stood, and all have worshipt me.

"Though many a town and house they made, and many a king's dwelling, Yet me they never did molest, to me no harm did bring: Then even as they did worship pay, so worship thou, O King!"

Then the king repeated two stanzas:

"But such another mighty trunk I never yet did see, So fine a kind in girth and height, so thick and strong a tree.

"A lovely palace I will build, one column for support: There I will place thee to abide—thy life shall not be short."

On hearing this the king of the gods repeated two stanzas:

"Since thou art bent to tear my body from me, cut me small, And cut me piecemeal limb from limb, O King, or not at all.

"Cut first the top, the middle next, then last the root of me: And if thou cut me so, O King, death will not painful be."

Then the king repeated two stanzas:

"First hands and feet, then nose and ears, while yet the victim lives, And last of all the head let fall—a painful death this gives.

"O Lucky Tree! O woodland king! what pleasure couldst thou feel, Why, for what reason dost thou wish to be cut up piecemeal?"

Then the Lucky Tree answered by repeating two stanzas:

"The reason (and a reason ’tis full noble) why piecemeal I would be cut, O mighty king! come listen while I tell. "My kith and kin all prospering round me well-sheltered grow: These I should crush by one huge fall,—and great would be their woe."

The king, hearing this, was much pleased:"’Tis a worthy god this," thought he, "he does not wish that his kinsfolk should lose their dwelling-place because he loses his; he acts for his kinsfolk's good."

And he repeated the remaining stanza:

"O Lucky Tree! O woodland king! thy thoughts must noble be: Thou wouldst befriend thy kindred, so from fear I set thee free." The king of the gods, having discoursed to this king, then departed. And the king being established according to his admonition, gave gifts and did other good deeds, till he went to fill the hosts of heaven.

The Master having ended this discourse said: "Thus it is, Brethren, that the Tathāgata acts so as to do good to his kith and kin;" and then he identified the Birth: "At that time Ānanda was the king, the followers of the Buddha were the deities which were embodied in the young saplings of the sal tree, and I was myself Lucky Tree, the king of the gods."